Copyright © 2018-2025 by A.I.

ETH Zurich, Switzerland

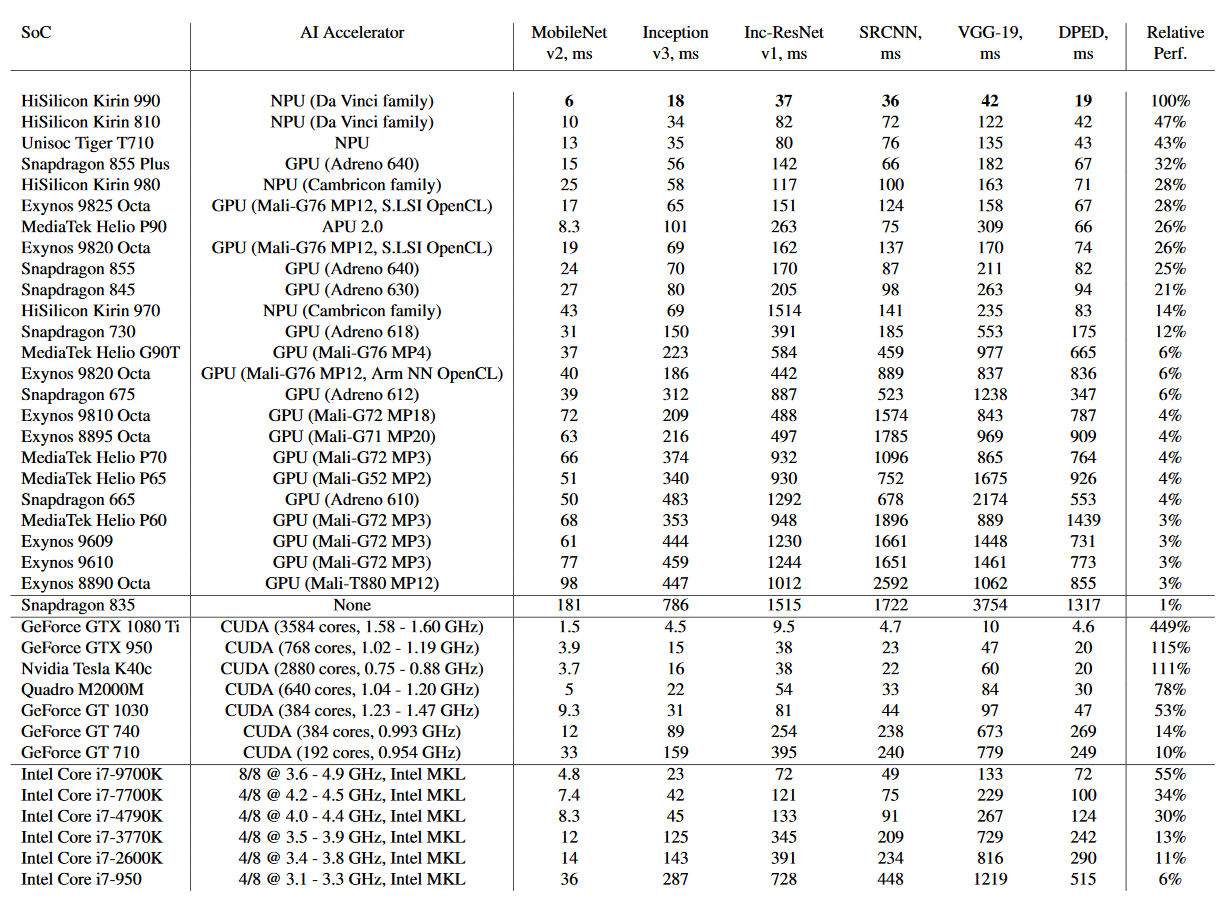

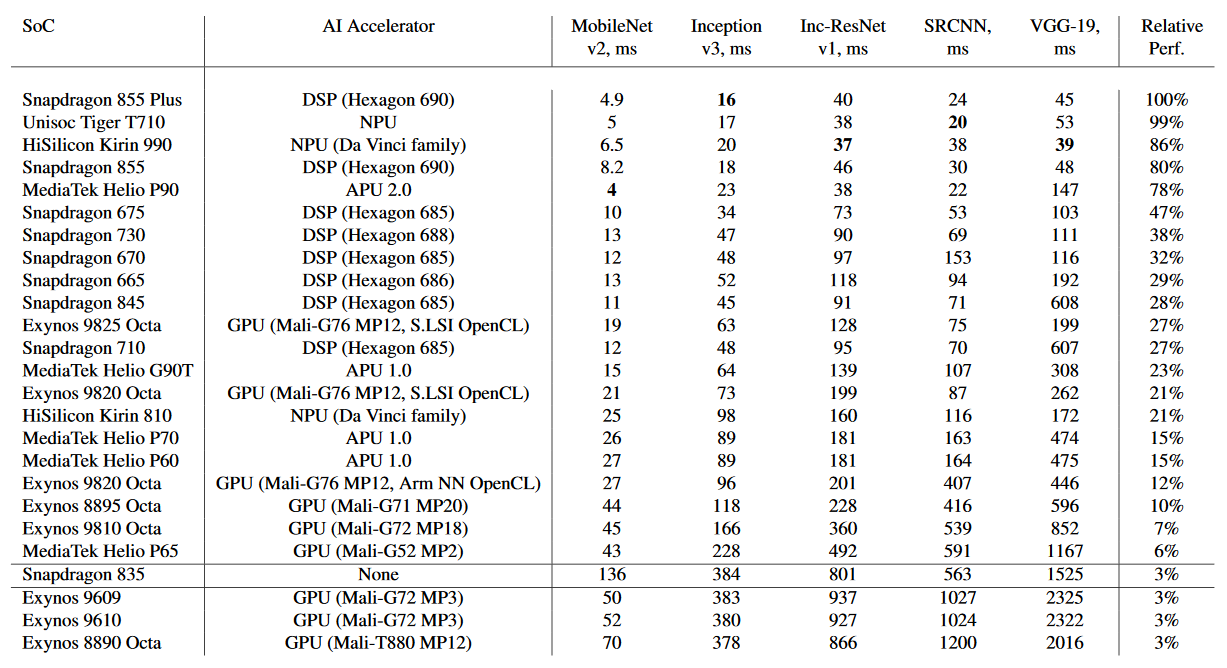

| Qualcomm: | Snapdragon 845 (acceleration: Hexagon 685 + Adreno 630); |

| Snapdragon 710 (acceleration: Hexagon 685); | |

| Snapdragon 670 (acceleration: Hexagon 685); | |

| HiSilicon: | Kirin 970 (acceleration: NPU, Cambricon); |

| Samsung: | Exynos 9810 (acceleration: Mali-G72 MP18); |

| Exynos 9610 (acceleration: Mali-G72 MP3); | |

| Exynos 9609 (acceleration: Mali-G72 MP3); | |

| MediaTek: | Helio P70 (acceleration: APU 1.0 + Mali-G72 MP3); |

| Helio P60 (acceleration: APU 1.0 + Mali-G72 MP3); | |

| Helio P65 (acceleration: Mali-G52 MP2); |

| Qualcomm: | Snapdragon 855 Plus (acceleration: Hexagon 690 + Adreno 640); |

| Snapdragon 855 (acceleration: Hexagon 690 + Adreno 640); | |

| Snapdragon 730 (acceleration: Hexagon 688 + Adreno 618); | |

| Snapdragon 675 (acceleration: Hexagon 685 + Adreno 612); | |

| Snapdragon 665 (acceleration: Hexagon 686 + Adreno 610); | |

| HiSilicon: | Kirin 980 (acceleration: NPU x 2, Cambricon); |

| Samsung: | Exynos 9825 (acceleration: NPU + Mali-G76 MP12); |

| Exynos 9820 (acceleration: NPU + Mali-G76 MP12); | |

| MediaTek: | Helio P90 (acceleration: APU 2.0); |

| Helio G90 (acceleration: APU 1.0 + Mali-G76 MP4); |

28 October 2019 Andrey Ignatov |

Copyright © 2018-2025 by A.I.

ETH Zurich, Switzerland